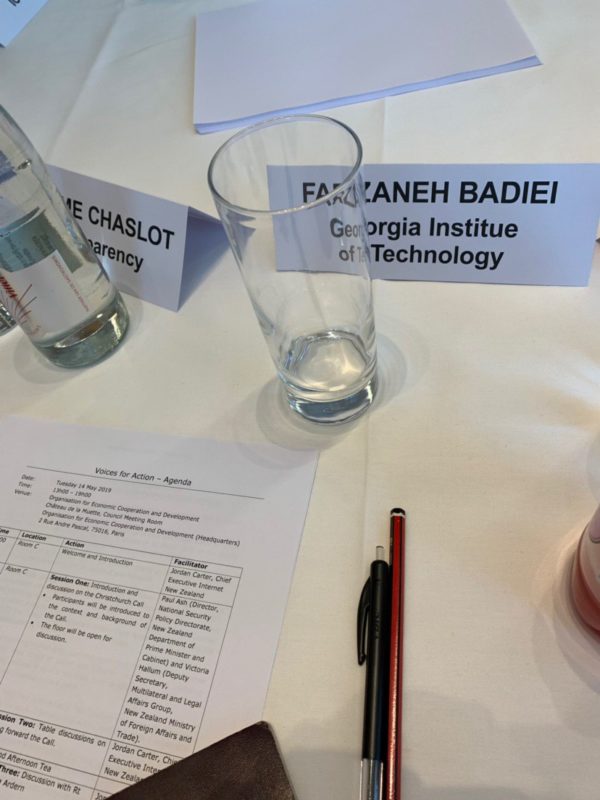

For the past few days, we have been working with other civil society groups on the Christchurch Call process. The Christchurch Call involves a summit between the big social media platforms and a number of governments held in Paris May 15, as part of a reaction to the terrorist attack in Christchurch. The effort is led by New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern who, in partnership with the French President, is seeking new forms of content regulation on social media platforms. A day before the summit there was a “Voices for Action” meeting between the Prime Minister and civil society groups, which we attended (see photo).

Misdirected focus

IGP understands the motivations underlying the Christchurch Call. We sympathize with the people of New Zealand who were shocked and scarred by the murders and the killer’s efforts to publicize his actions on the Internet. But the overwhelming emphasis on social media that this process is promoting seems to us to be badly misdirected. Preventing uploads or erasing the messages of terrorist groups from social media platforms is not the same as preventing terrorist acts or protecting innocent people from hate-inspired violence. And major social media platforms are not the only way terrorists communicate. A false equation between terrorists’ use of platforms and terrorist acts seems to underlie much of the post-Christchurch dialogue, and it needs to be challenged.

At this time, we should not be having a conversation dominated by the topic of social media regulation. We should instead be having a conversation about intolerance, racism, nationalism, and other tribalist or collectivist groups who are likely to carry out violent attacks. We should be discussing how to mitigate violence and what methods governments can use to better protect the potential victims of terrorist acts. In other words, actual terrorism and violence, and the groups that carry out such acts, should be the primary targets of our response, not the Internet. Instituting aggressive new forms of prior restraint on speech will not undo the crime that was done, nor is there any reason to believe that it will prevent new terrorist acts from happening in the future.

The process

As a global Internet Governance process, the Christchurch Call falls short of best practice. It was set up as a government-led initiative designed to allow states to pressure private platform providers to execute a predetermined agenda of stronger and more extensive content controls.

We appreciate the efforts of InternetNZ to include civil society groups in the process; without their principled efforts, civil society would have been excluded entirely. As it is, some governments are still resisting civil society inclusion. The leaders of the process refused to share the text of the proposed Pledge until the last minute. It is still embargoed and civil society will not be included in the finalization of the text. It is not clear what will happen to the input provided today during the Voices for Action meeting, but is likely it will not have any impact on the current pledge text, which will be discussed and signed tomorrow during the Christchurch call meeting. The Christchurch call summit that will happen tomorrow (15 May) is co-moderated by Prime Minister Ardern and President Macron and only includes around 8 member states and big technology corporations. Prime Minister Ardern reassured us today that this is not the end of the process and we will have more opportunities to get engaged. But if the pledge text is not workable for most of us, in the future we will need to reopen the issue.

To her credit, Prime Minister Ardern seemed to understand the problems with the process and asked us how to lead it better in the future. We believe that multilateral processes are not acceptable for matters dealing with Internet governance issues. Even if they allow various stakeholder groups to participate they would never be on equal footing with the states. The New Zealand government has been very careful not to work with Human Rights violating member states of intergovernmental organizations, but that is not enough. Multilateral processes inevitably lead to including member states and excluding other nongovernmental actors. If this pledge is discussed in the UN general assembly, for example, we cannot exclude human rights-violating member states. Also, some countries that are obvious human rights violators are not recognized as such by their allies. Moreover, we need to consider that some developed countries have started to weaken the rule of law and democracy on the Internet. The New Zealand Prime minister is also going to meet with the King of Jordan about the Christchurch call.

All in all, while the exclusion of human rights violators might not happen, inclusion of other actors can be achieved by giving a chance to nongovernmental actors other than big tech corporations to participate effectively and get involved with the negotiations. That way we can overcome the power imbalance and dilute the power of states that don’t believe in the interoperable, open and globally connected Internet.

The worst of both worlds?

One problem with these initiatives is that it places free speech advocates in a netherworld between public and private authority. It is one thing if private platforms are empowered to moderate the content they publish. We might not like the choices they make but at least they are accountable in some ways to the market and their end users. People can abandon them if they go too far or become too arbitrary and there could be some diversity among platforms’ policies. On the other hand, if governments attempt to censor directly, then in liberal democracies at least there are legal and due process constraints on what they can do. But when governments conspire to pressure platforms into restricting expression, we get the worst of both worlds. We get government action without the constraints of law; we get the efficiency and discretion of a private actor without the discipline of a competitive market. The Christchurch Call contains several references to the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT). It seems the GIFCT is already doing most of the things the New Zealand PM is asking for.

Limiting the scope of the Call

The pledge text refers repeatedly to “online service providers” and calls upon them to commit to a range of actions, from prevention of uploads to content take down. We agree with the civil society statement that the term “online service provider” is too broad. These content regulation measures should not include all forms of Internet infrastructure. While social media platforms can be a better term we need to consider that these platforms provide messaging services . Does this mean that encryption might be endangered? Or more broadly could preventative measures endanger anonymity on the internet? The New Zealand government has assured us that the scope will be limited so that it doesn’t include internet infrastructure nor encryption.

Defining ‘terrorism’ and ‘extremism’

After the fact, when a terrorist act has happened or a terrorist group has been established, it is easier to categorize the act as a terrorist attack. Not all attacks are going to be as obviously terroristic as the Christchurch attack. Not all extremist content is going to incite violence or terrorism. And not all violent videos are going to be of the same nature as the Christchurch attack. The definition of terrorism depends who is defining it, what processes are used, and what political conflicts are involved. Therefore, national laws are not suitable for defining terrorism with global implications because they will be entangled with political and inter-state conflicts. There was a good suggestion during the meeting to define terrorism through a collaborative process including all governmental and nongovernmental actors so that we can reduce the political biases and lobbying that happens at the national level.

Is elimination of “terrorist, violent extremist content” the answer?

The pledge seems to be putting forward the elimination of terrorist content as a way to fight terrorism. But elimination of content does not eliminate terrorism and violence. Quite the contrary, the availability of such content might help identify dangerous groups, or discourage people from getting involved with terrorists. The videos can be used in courts as evidence. While removal of explicit attacks videos might make sense these kinds of videos can be identified with certainty only after the attack. Prevention of production and dissemination of such content is an ex ante call that will affect freedom of expression. During the meeting some argued that it is promoting such content by algorithms that is problematic and content removal is not really an effective measure to stop amplification of such content.

Global, open and secure Internet

The pledge mentions that governments and tech corporations should adhere to the principles of an open and secure Internet. We find these reassurances unconvincing. If these principles are not adhered to we are going to take away the cross border nature of the Internet with multilateral initiatives. States routinely securitize their borders and hamper freedom of movement with arguments about countering terrorism and bringing security to their citizens. In multilateral processes about countering terrorism online, they might make similar arguments. During the meeting it was mentioned that social media can be used as a weapon. This is a dangerous proposition which can have unintended consequences. It is equating the social media problem with major national security issues. When national security is invoked, it can lead to overly restrictive approaches to expression.

Collective action and the Internet community

We learned a good lesson about Internet community cooperation during the Christchurch process. With the rise of multilateral initiatives and the ever-growing desire of states to regulate the internet, the community needs to work together and take collective action. Many parts of the community have had many collaborations with big technology corporations. Surely big technology corporations could have considered civil society input in this process. Moreover, just paying lip service to human rights by the governments is not enough. They need to show such commitment by fighting to include the Internet community in discussions and refrain from holding these talks in silos limited to big tech corporations.

The civil society and some parts of the technical community succeeded to provide their input for this process. We would have liked to have seen the Internet Society take a more active role, however. Moreover, there were some civil society organizations that had access to the pledge text but did not leak it to their peers. We were asked during the meeting what processes are better to discuss issues related to the elimination of terrorist content online. Perhaps a new process which is a continuation of the collaboration effort InternetNZ set in motion might be more suitable than sporadic, closed or single stakeholder efforts. Overall the way to fight with multilateral processes that try to control the internet and have an open, secure and globally connected internet is to work together setting up processes and institutions.