October 15, 2021

Free expression advocates win Nobel Peace Prize

The 2021 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to journalists Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Dmitry Muratov of Russia. Announcing the award, The Nobel Committee clarified that the two working reporters were chosen for the award because they represent “a golden standard” of “journalism of high quality”, and stressed that “without media, you cannot have a strong democracy.” The recognition is important because of the threat both journalists face in their respective countries. Muratov is the co-founder of Novaya Gazeta, described as “the most independent paper in Russia today” by the Nobel Prize Committee. Several of Muratov’s colleagues have been slain for their work criticizing Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Ms Ressa in 2012 co-founded Rappler, a news website that has focused “critical attention on the (President Rodrigo) Duterte regime’s controversial, murderous anti-drug campaign. She and Rappler have also documented how communication media are used by authoritarian states to spread fake news, harass opponents and manipulate public discourse.

ISOC asks EU to regulate the internet

On October 4, 2021 the Internet Society submitted comments recommending that the European Commission make compulsory unspecified elements from its Mutually Agreed Norms on Routing Security (MANRS) initiative. The comments were filed as part of the EC’s Revised Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems (NIS 2) proposal, which will govern in part European-based critical infrastructure-like entities and large digital services. Currently, to become MANRS “conformant” and an eligible participant, network operators must prevent propagation of incorrect routing information, prevent traffic with spoofed source IP addresses, facilitate global operational communication and coordination, and facilitate routing information by publishing and maintaining intended

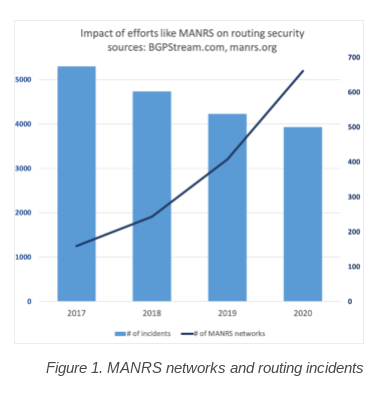

routing announcements in routing registries or valid route origin objects. But all of the above practices are done on a voluntary basis by operators. As this Figure published by ISOC shows, operator participation has grown substantially over the past several years as they are continually faced with routing security issues and have economic incentives to adopt these practices. More importantly, adoption appears to be associated with declines in the number of routing security incidents.So why advocate the need for incorporating elements of MANRS in NIS 2? To date, there is no language in NIS 2 that concerns routing security specifically. The term “routing security” failed to make the Jan 2021 Summary Report on the open public consultation. However, in May the European Parliament’s Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE) filed comments proposing language that “interoperable secure routing standards [like RPKI] should be promoted”. So, if there is only demand coming from some obscure political committee, what’s going on?

routing announcements in routing registries or valid route origin objects. But all of the above practices are done on a voluntary basis by operators. As this Figure published by ISOC shows, operator participation has grown substantially over the past several years as they are continually faced with routing security issues and have economic incentives to adopt these practices. More importantly, adoption appears to be associated with declines in the number of routing security incidents.So why advocate the need for incorporating elements of MANRS in NIS 2? To date, there is no language in NIS 2 that concerns routing security specifically. The term “routing security” failed to make the Jan 2021 Summary Report on the open public consultation. However, in May the European Parliament’s Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE) filed comments proposing language that “interoperable secure routing standards [like RPKI] should be promoted”. So, if there is only demand coming from some obscure political committee, what’s going on?

The Commission is already proposing to impose onerous regulations in other areas. According to Recital 15, 12019/21, “all providers of DNS services along the DNS resolution chain within scope, including: (1) operators of root name servers, (2) top-level domain (TLD) name servers; and (3) authoritative name servers for domain names and recursive resolvers” are within scope of NIS 2. NIS 2 could fundamentally alter the DNS governance landscape, specifically concerning registration data. Recitals 59-64, 12019/21 would impose requirements on all DNS service providers to collect domain name registration data by implementing legal (e.g., jurisdiction), technical, and organizational measures. Recital 23, 12019/21 would require TLD registries to reply to requests from legitimate access seekers for the disclosure of domain name registration data within 72 hours.

The Info Ops on Facebook

Facebook’s troubles are multiplying. The social media giant suffered a 5-hour, global outage, as Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp were taken offline due to mismanagement of its BGP routing announcements, which eliminated access to its domain nameservers. But that was actually less damaging than two information operations conducted against the company this month by non-state actors. Two weeks ago, The Wall Street Journal published The Facebook Files detailing the social media giant’s internal practices and approach to content moderation. The Files were based on internal documents that were leaked by Frances Haugen who had previously worked on Facebook’s civic misinformation and counter-espionage teams. Haugen copied and leaked hundreds of pages of internal reports to the press, reminiscent of Snowden and Assange. But there will be no exile or prison for Haugen. In what was clearly a well-planned and fully lawyered operation, she revealed her identity, sought shelter from SEC whistleblower laws, and was treated to a triumphalist Congressional hearing and widespread coverage by the public media.

Haugen accused Facebook of prioritizing “profits over safety” and labelled decisions being taken inside Facebook as “disastrous for our children, public safety, privacy and democracy”. Haugen also drew attention to the lack of transparency about what goes on inside Facebook and called for legislators to introduce “real oversight” by allowing researchers to validate Facebook’s data and its systems.

The Haugen/old media/Congress gambit massively amplified the flawed narrative that social media creates, rather than makes visible, social conflicts and psychological problems, reasserting the tired claim that Facebook profits by algorithmically rewarding engagement founded on divisive and hateful content, and that these problems could all be solved if there was just more content moderation and/or regulation. Conservative Republicans and progressive. Democrats joined hands in promoting this narrative. The operation advanced a specific agenda: to build support for regulating Facebook and further undermining Section 230. In addition to Haugen’s testimony, there have been reports of a second whistleblower willing to testify regarding foreign national leaders’ manipulation of the Facebook platform.

The Haugen narrative, which implies that government regulators should tell Facebook what to suppress, was undercut by yet another leak of internal documents: The Intercept on October 12 provided a list of more than 4,000 groups and individuals that Facebook classifies under “terror,” “hate,” “crime,” “militarized social movement” or “violent non-state actor” designations and uses to block accounts or content. What makes this list problematic for the “Facebook needs regulation” narrative is, first, that Facebook is already filtering tons of bad actors and content, apparently sacrificing the huge profits that would allegedly be generated by public engagement with it, but also that the list is quite plainly a reflection of what the US government (and to a lesser degree, European governments) want. As the Intercept wrote, “The list and associated rules appear to be a clear embodiment of American anxieties, political concerns, and foreign policy values since 9/11.”

For many years now, researchers and digital rights activists have been demanding more transparency about its list of dangerous individuals and organizations. In January Facebook’s Oversight board overturned a decision to remove a post the company said violated this policy, noting the “rules were not made sufficiently clear to users.” The board had also recommended that Facebook publicize its list of dangerous organizations and individuals or list examples. Now that the list has been exposed, leftist critics think the list is too lax on rightwing groups, and rightwing groups no doubt think the opposite. It is not at all clear that more oversight, transparency and external regulation will make the world satisfied with the communicative forces unleashed by social media platforms.