On October 6th a letter was circulated to the negotiators preparing for the World Trade Organization’s 11th Ministerial meeting (MC11), which will be held December 10-13, 2017 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The letter purports to speak for all of “global civil society,” and singles out for attack the prospect of an agreement on e-commerce trade, which it calls “a dangerous and inappropriate new agenda.” A large part of the text appeared several months ago as part of a Huffington Post op-ed written by Deborah James, a Director at the anti-free trade Center for Economic and Policy Research. In response to this letter, IGP wishes to make the following points:

Not the voice of “global civil society”

That statement is not the voice of “global civil society.” It is an alliance of labor unions primarily, with support from some anti-globalization environmental and church groups. While these are legitimate stakeholders who deserve to be heard, we wish to challenge the advocates’ pretense that consumers, civil society groups and the developing world all oppose free trade in e-commerce and only U.S.-based big corporations favor it and benefit from it.

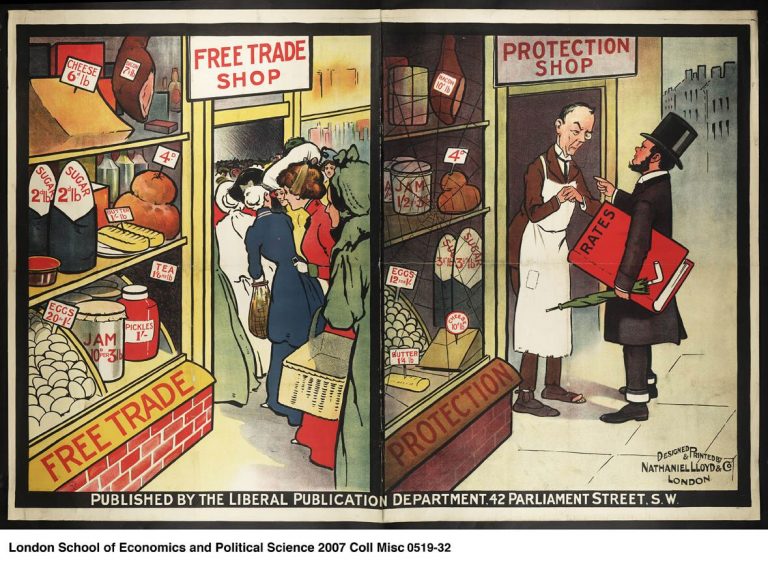

There is a strong case to be made that free trade, while having complex distributional effects, improves consumer welfare overall and vitalizes developing economies. And it is hard to see why civil society should be defending protectionism and the associated regulations. They often stifle economic growth and are inevitably exploited by vested interests and corrupt government officials to enrich themselves at the expense of end users and consumers. We favor an open and honest debate about the merits of Internet-enabled trade in services, a debate that should be evidence-based and not based on the false polarity between “big corporations” and “the people.” Many in civil society support digital free trade.

There is a strong case to be made that free trade, while having complex distributional effects, improves consumer welfare overall and vitalizes developing economies. And it is hard to see why civil society should be defending protectionism and the associated regulations. They often stifle economic growth and are inevitably exploited by vested interests and corrupt government officials to enrich themselves at the expense of end users and consumers. We favor an open and honest debate about the merits of Internet-enabled trade in services, a debate that should be evidence-based and not based on the false polarity between “big corporations” and “the people.” Many in civil society support digital free trade.

E-Commerce trade

As participants in Internet governance, we disagree profoundly with the attack on free trade in e-commerce. The policies advocated in the statement – particularly data localization requirements and highly regulated cross-border data transfers – would reinforce current tendencies towards the political and technical disintegration of global communications. Whether intended or not, the statement’s opposition to open and competitive trade in e-commerce services lends support to the economic nationalism of China’s Xi, Russia’s Putin and America’s Trump. It is similar in logic to and motivated by the same spirit as the right-wing anti-immigration parties of North America and Europe. In Trump’s “wall,” in Brexit, in China’s “internet sovereignty” initiatives and Russia’s data localization law we are starting to see the effects of a more bordered information economy, and they do not look pretty.

Trade and human rights

In addition to their harmful economic effects, barriers to e-commerce can have severely negative effects on human rights. Data localization gives authoritarian governments easier access to user data for surveillance and law enforcement purposes. By denying Internet users the ability to access external email or web-based services, data localization rules can strengthen authoritarian states’ control over the internet and can even put dissident users’ lives at risk. While trade agreements all have shortcomings, various studies attest to the benefits of freer trade for protecting human rights and strengthening democracy.[1] Trade agreements can incentivize nation states that do not have appropriate data protection laws in place to pass legislation. Trade agreement negotiators, despite the allegations, have paid attention to privacy protection. There are relevant sections in TPP that require the parties to the agreement to protect personal information.[2] The negotiation of the Cross-Border Privacy Rules in the APEC countries was used by privacy advocates to improve privacy protections in cross-border e-commerce.[3] The potential contribution of trade agreements to enhancing rule of law and protecting digital rights have always been ignored by anti-trade civil society organizations.

Examples

Numerous case studies illustrate how restrictions on the market for ICT services stunt development and hurt consumers, and when these restrictions are eliminated developing economies benefit. Here are a few examples:

- South Africa’s Telekom monopoly fought for years to keep competitors financed by foreign capital out of the market, so as to preserve their monopoly profits and labor union control of employment. When Telekom was given a 5 year monopoly in 1997, its prices were so high that telephone subscription rates declined. Lacking competitive incentives, it failed to expand service to new areas rapidly. In 2008 South Africa’s communications minister was involved in numerous legal battles to try to stop Internet service providers and other companies from building their own networks. The Telekom monopoly, the trade union confederation and the national regulator, ICASA, worked together to try to block entry of Vodacom into the market in 2009. Fortunately, the courts thwarted them. After new competition from foreign-financed or partially foreign-owned companies entered the market, interconnection fees and consumer prices fell, and internet and telecom development took place more rapidly.

- In India, Internet service provider (ISPs) are not allowed to interconnect Voice over IP services to the public telephone network. This means that Internet-based calls cannot be mixed with traditional landline and mobile calls.The Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of India openly justifies this regulation on the grounds that it does not want users to bypass the telephone companies tolls; in other words, consumers pay millions more for service than they need to simply to protect the incumbent telephone company.

- Mexico City, home to the largest taxicab fleet in the world, has seen violent confrontations between ride-hailing apps and official taxi drivers because the new competition has reduced prices for consumers. When the Association of Organized Taxi Drivers blocked streets in protest, the hashtag #UberSeQueda, or “UberStays,” became a trending topic on Twitter. According to a Wall Street Journal article, “Supporters of the alternative car services posted complaints against Mexico City’s notoriously aggressive taxi drivers, saying drivers will often tell passengers “I don’t have change,” “the taxi meter is broken,” or “I don’t go there.”” Clearly, what is seen as disruptive to the established taxi drivers is seen as improvement by many consumers and as better opportunity by the tens of thousands of new drivers who have been able to find a job. Mexico City also represents an example of how the new market entrants are expanding taxi service from urban to suburban areas, including less wealthy and historically underserved areas.

- The facts about the WTO’s Information Technology Agreement (ITA) counter the statement’s distorted view that trade agreements subjugate developing economies to the needs of richer countries. The ITA completely eliminated most tariffs on ICT equipment. Studies show that joining the ITA spurs the adoption of productivity-enhancing ICTs across all sectors of an economy and that the growth and development benefits over time far outweigh the short-term loss in tariff revenues.[4] A long-term assessment shows that free trade increased the role of developing economies in global information technology production networks. The share of developing and emerging economies in the world trade of ITA goods grew rapidly over the period 1996-2015, at the expense of the mainly developed world signatories.[5]

It is time for global civil society organizations to break free of knee-jerk anti-market assumptions and look at the facts regarding digital trade.

[1] Hafner-Burton, E.M., 2005. Trading human rights: How preferential trade agreements influence government repression. International Organization, 59(3), pp.593-629. Hafner-Burton, E.M., 2013. Forced to be good: Why trade agreements boost human rights. Cornell University Press; Milner, H.V. and Kubota, K., 2005. Why the move to free trade? Democracy and trade policy in the developing countries. International organization, 59(1), pp.107-143; Rudra, N., 2005. Globalization and the Strengthening of Democracy in the Developing World. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 704-730.

[2] TPP, e-commerce section, Article 14.8, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Final-Text-Electronic-Commerce.pdf

[3] Chris Connolly, Graham Greenleaf and Nigel Waters. (2015) “Privacy groups win changes to APEC CBPR system.” 133 Privacy Laws & Business International Report, 32-33 (February) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2603530

[4] Stephen Ezell and John Wu, How Joining the Information Technology Agreement Spurs Growth in Developing Nations. ITIF, May 22, 2017. https://itif.org/publications/2017/05/22/how-joining-information-technology-agreement-spurs-growth-developing-nations

[5] World Trade Organization, 20 Years of the Information Technology Agreement: Boosting trade, innovation and digital connectivity. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/ita20years_2017_chap1_e.pdf

Dear Milton,

I’m one of the co-signer of that letter. I’m not associated with trade unions, nor with environmental or church groups. I used to defend the WTO against left-wing criticism, but that was before the WTO degenerated into an instrument of corporate lobbing.

Free trade can improve consumer welfare, but it has to be really free trade, not a masquerade that permits dominant private companies to exploit their market power to impose unfair terms and conditions, and to avoid paying taxes.

I am not defending protectionism, I am combating corporatism.

You say that you want an open and honest debate. But, as you know, WTO is anything but open. So I’m surprised that you, a staunch advocate of multi-stakeholder processes, are not outraged that matters with are directly related to the Internet, such as spam, are being proposed for discussion in WTO, the least transparent and least inclusive intergovernmental organization that I know of.

You are correct to note that data localization can have negative effects on human rights. But so can the proposed free flow of data. I disagree with when you say that trade agreement protect privacy: in my view (and that of others), what is being proposed will not sufficiently protect privacy.

As you say, we need an open and honest debate, but we are not going to get it in WTO. So I would urge you to join us in calling for no such discussions in WTO, at least not until WTO becomes transparent and inclusive.

Regarding your examples, when you defend Uber, are you implying that labor protection laws should be ignored? That is, no health insurance benefits, no social security benefits, etc.? Do you believe the fiction that Uber drivers are real independent contractors, or do you believe that there should be no labor protection laws?

Best,

Richard

Your response is addressed to us as IGP, Richard. So I’d like to ask you a question and make a comment. You say :

“I disagree with when you say that trade agreement protects privacy: in my view (and that of others), what is being proposed will not sufficiently protect privacy.”

What does sufficiently mean by your group? European heaven? or developing countries dystopia with some kind of civil society groups?

And no, trade agreements negotiations cannot be always transparent. That does not mean we should not get our principles right!

Dear Farzaneh,

In my view, the old EU Directive on data protection was about right and would have been a good basis for a global data protection regime. I’m skeptical about the GDPR, in particular because of its likely extra-territorial effects. And, in order to protect privacy, we would need additional instruments, restricting surveillance to what is necessary and proportionate, and committing states not to weaken or prohibit encryption.

Why shouldn’t trade negotiations be transparent? They are supposed to be win-win. In win-win negotiations, secrecy is not needed. Secrecy is typically used in win-lose negotiations. So a call for secrecy in trade negotiations is an implicit acknowledgment that such negotiations are not win-win.

Finally, how can we “get our principles right” if negotiations are carried out in forums that are not inclusive and where civil society has no voice?

Best,

Richard

In principle, I agree with many points raised in the commentary. However, this statement stacks too many issues into a same basket:

“As participants in Internet governance, we disagree profoundly with the attack on free trade in e-commerce. The policies advocated in the statement – particularly data localization requirements and highly regulated cross-border data transfers – would reinforce current tendencies towards the political and technical disintegration of global communications.”

Due to reasons not worth spelling out (hint: NSA), any comment about data localization originating from the US will be taken with justified skepticism anywhere in the world. In my opinion, things like GDPR are a big step toward the right direction of *multi-stakeholderism* w.r.t. data.

(Judging from the recent Equifax-case, maybe it would be also a good idea to first fix the huge domestic data-mess before proposing global solutions…)

The idea that data localization protects you from the NSA seems to have arisen with the Snowden revelations. But it should have died with the Snowden revelations, because if you look at the materials he released you realize that NSA has thousands of CNE points around the world and storehouses of zero-days that allow it to break in to targets. American companies and citizens have more protections from NSA surveillance than non-citizens and overseas facilities. The geographic location of data as very little to do with its security; what matter is the technical strength of its security. Data localization simply facilitates legal access by the local government.

I agree about the point regarding security, but that kind of misses the mark. The real implications of Snowden are political. Given the currrent Microsoft-ECPA case, clearly the issue of surveillance-versus-data-localization is sensitive also in the US, despite of NSA’s superpowers. Btw, zero-days have nothing to do with mass surveillance.

The problem with this piece is that you are pretty much directly echoing the US standpoint to WTO and related trade agreements. The “internet freedom rhetoric” is also what many strategic analysts have recommended for the Trump administration.

The US position may be a good position or even the best position, but it still cannot escape the fact that the US is nowadays pretty much alone pursuing the laissez faire of data localization and privacy. Many of the problems could be solved if the US would align itself toward rest of the world in the data localization and privacy regulations. This does not seem to be realistic in the current political climate, unfortunately.

Good points. People who are interested in the data protection issue and how it could be addressed at the international level may wish to read section 1 of my most recent submission to the UN Working Group on Enhanced Cooperation. It is at:

http://www.apig.ch/Gaps%20r8%20clean.pdf

I sent this correction request to Farzaneh Badiei yesterday afternoon (including links so that she could readily verify the information). Hopefully she and IGP can correct this soon:

Dear Dr. Badiei,

Greetings from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington, DC. I am writing to request a correction to two factually incorrect claims on your posted statement, “Civil Society and Digital Free Trade: A Response.”

The statement reads that CEPR “is funded primarily by labor unions.” This is false. As stated on our website, and readily available in our filings with the IRS, we receive most of our funding from foundations, with labor union support comprising a much smaller proportion of our budget (under 4 percent of our revenue in 2016).

The statement also describes CEPR as “anti-free trade.” While it may be your opinion that we are not sufficiently supportive of “free trade,” as an objective matter, we routinely advocate for free trade in a number of areas. We are well known for advocating against many of the current, harmful, and costly protections of digital creative work, for example. We have repeatedly called for ending protections for highly paid professions such as doctors and lawyers. And we regularly call for ending harmful patent and copyright protections that drive up the cost of medicines, to take a few examples.

In the digital sphere, we have practiced what we preach; we have made books that we have published ourselves available for free online. Almost all of our work is available through a Creative Commons license.

We look forward to seeing these descriptions of CEPR corrected on your website.

Thank you for your attention.

Sincerely,

Dan Beeton

International Communications Director

Center for Economic and Policy Research

Dan: we have corrected the assertion about funding, though major unions do comprise 7 of the 26 supporters listed on your website. I would still have to characterize CEPR as largely anti-free trade. While we appreciate and welcome your stance against copyright overreach and protectionism in professions, the October 6 letter is obviously a broadside against free trade in a variety of sectors and adheres to the general philosophy that protectionism and “sovereignty” is a successful path to development.

I disagree that the letter in question is a “broadside against free trade” . It is a broadside against agreements and proposals which favor corporate interests and the creation of dominant market power under the guise of favoring free trade.

WTO was supposed to be about reducing customs duties and other barriers to trade. But it has turned into a global regulator for matters which are not obviously related to trade. And it enforces those regulations through its binding dispute settlement system.

For example, WTO agreements allow developed countries to continue to subsidize their agricultural sector, while preventing developing countries from doing so. WTO agreements require developing countries to impose intellectual property regimes that are similar to those of developed countries.

Closer to what concerns the Internet, the GATS Annex on Telecommunications imposes rules on what states can and cannot do with respect to certain telecommunication services: that is a form of regulation. And the WTO Reference Paper on telecommunications goes into somewhat greater detail (note that its preamble reads “The following are definitions and principles on the regulatory framework for the basic telecommunications services”).

Even closer to what concerns us, there are proposals to WTO regarding spam, data flows, e-signatures, etc. (How is spam related to trade?)

Further, the agreed TPP text contains provisions regarding many matters that affect Internet. In some cases, the TPP text is similar to proposals that were made to ITU, but rejected in ITU by some of the very same countries that adopted TPP (but note that the USA has rejected TPP). You can find an outline of the overlap between ITU and trade negotiations in section 3 of my paper at:

http://www.apig.ch/Trends%20for%20WGEC.pdf

Now I fully understand that some, in particular some industry representatives, believe that the WTO provisions are very good and should be supported.

But that’s not my point: my point is that the WTO regulates. So folks

that think that the WTO regulations (e.g. stronger intellectual property protection) are not appropriate should be able to influence the discussions. But that is hard at present, because WTO is not very transparent.

So why should we support secret discussion in WTO of matters that affect all of us?

I would not want readers to be left with the impression that criticism of holding discussion of Internet matters in WTO and other trade negotiation forums is recent or restricted to the 300 signatories of the letter cited by Milton.

I refer to pp. 74-75 of UNCTAD’s Information Economy Report 2017:

Digitalization, Trade and Development, at:

http://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=1872

It cites the Global Commission on Internet Governance:

“Bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements can significantly affect Internet governance issues. Many, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, specifically address important issues such as data localization, encryption, censorship and transparency, all of which are generally regarded as forming part of the Internet governance landscape. However, they are negotiated exclusively by governments and usually in secret. At the same time, such agreements substantially benefit the Internet in a myriad of ways, such as by agreeing on rules to improve competition and market access. Further agreements such as the US-Europe Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the Trade in Services Agreement under the World Trade Organization are expected to cover similar territory. The fact that these negotiations are open only to governments has inspired protests by non-governmental actors demanding that they be informed and engaged in negotiations to allay fears that the new rules embedded in these agreements favour the interests of governments or corporations over those of other Internet users. The closed nature of the negotiations also means that the benefits governments hope to achieve may not be evident to the general public (GCIG, 2016: 78).”

And the Open Digital Trade Network Brussels Declaration,at:

https://www.eff.org/files/2016/03/15/brussels_declaration.pdf

“We recognize the considerable social and economic benefits that could flow from an international trading system that is fair, sustainable, democratic, and accountable. These goals can only be achieved through processes that ensure effective public participation. Modern trade agreements are negotiated in closed, opaque and unaccountable fora that lack democratic safeguards and are vulnerable to undue influence. These are not simply issues of principle; the secrecy prevents negotiators from having access to all points of view and excludes many stakeholders with demonstrable expertise that would be valuable to the negotiators. This is particularly notable in relation to issues that have impacts on the online and digital environment, which have been increasingly subsumed into trade agreements over the past two decades.”

In addition, the cited UNCTAD report says:

“Stakeholders have also expressed concerns about various substantive aspects of rules governing trade in the digital economy. Contentious issues include the inclusion of provisions concerning intellectual property, encryption, source codes, intermediary liability, network neutrality, spam, authentication and consumer protection.”

UNCTAD gives the following as the source for that statement:

“Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs (BEUC), Analysis of the TiSA e-commerce annex & recommendations to the negotiators, TiSA leaks, September 2016 (http://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2016-083_lau_beucs_analysis_e-commer

ce_tisa_2016.pdf , accessed 1 June 2017); and EDRi’s red lines on TTIP, January 2015 (https://edri.org/files/TTIP_redlines_20150112.pdf , accessed 1 June 2017). BEUC and EDRi are coalitions of 43 and 35 civil society organizations, respectively.”

I would push back on the notion that there is a false polarity between big corporations and the people. While it can be said there are benefits of free trade that are gained for all, we must also carefully analyze the benefits that corporations gain relative to the benefits of “the people.” If there are built in corporate biases, then free competition destroys itself and economic dictatorship supplants the free market, leaving poverty and inequality in the areas it seeks to serve.

To do this, we need to learn our lessons from past trade deals, such as NAFTA. Has NAFTA been a success? It depends on who you ask. Ask any corn, bean or rice farmer in Mexico if free trade was good for them. 3 million corn farmers in Mexico with income of 1959 pesos a month in 1991 became 1.7 million corn farmers with income of 228 pesos a month in 2003. A nation that was self-sufficient in corn production is now forced to import corn to feed itself.

If you look at Mexico national statistics, from 1960-1980 (pre-NAFTA), Mexican real GDP per person almost doubled, growing by 98.7%. From 1980-2000 it was 15.6% and from 2000-2013 it was 8.2%. Compare that to other Latin American countries, which grew 91.1% from 1960-1980, 7.7% from 1980-2000 and 28.7% from 2000-2013. If you look at specifically the 20 years following NAFTA, from 1994-2013 Mexico growth was 18.6% and Latin American growth was 35.4%.

The poverty rate in Mexico stayed the same, 52.4% in 1994 versus 52.3% in 2012, If you look at the region, though, it fell from 43.9% in 2002 to 27.9% in 2013. These are Mexico’s national statistics. If you look at ECLAC statistics, Mexico’s poverty rate falls from 45.1% in 1994 to 37.1% in 2012. But in the rest of the region, excluding Mexico, it falls from 46% to 26%, two and a half times as much.

So, Mexico, with their developmentalist and protectionist policies of the pre-1980 period went from growth rates higher than Latin American to lower growth rates after NAFTA while eliminating poverty 60% below the rate of the rest of Latin America.

Domestically, NAFTA’s effect on farmers have not been stellar either. Small and mid-size farmers have been substantially hurt, and been forced to either consolidate and go big or get out. Many who stayed in were able to, not because of natural market forces, but by subsidies provided by the government. The number of mid-sized farms fell by 40% from 1982 to 2007. Meanwhile, the share of Tyson, Cargill, JGF and National Beef (top 4) in total beef production increased from 69% in 1990 to 82% in 2012, and is 85% now. The same goes for many other sectors. Fewer firms are gaining market share. 20% of farms now operate 70% of U.S. Farmland.

We must be honest with ourselves that even well-intended globalization tends towards this go big or get out dilemma. This can have a harmful effect on the middle class and actually create poverty. So, in some cases, protectionist policies are beneficial.

With regard to data localization, While it is true that data localization would give authoritarian governments easier access to user data for surveillance and law enforcement purposes, it would also limit the ability of non-authoritarian governments to constrain corporate behavior in the public interest. You are correct when you state that “Data localization gives authoritarian governments easier access to user data for surveillance and law enforcement purposes.” The same, however is true when you have a foreign power (corporate or government, national or international) which has easier access to that user data. They could use it for the same evil purposes for which authoritarian governments could.

You make several valid and important points with regard to the technical disintegration of global communications and the creation of a more bordered information economy. With regard to economy, I agree this is a negative. However, so is the harmful effect on the middle class and increased poverty of certain industries and even countries that open themselves up to unfettered free trade.

The principal issue, however, is if there should there be a mandate that WTO members negotiate new global rules on e-commerce. The issues being discussed have either already been resolved or are in the process of being resolved in other forums. However, agreements among countries in forums such as G20 don’t have the power of binding countries to act, and since TPP, TTIP and TISA are currently going nowhere, they want to use the WTO to mandate these new global rules. So, the first problem is the forced mandate, rather than a more organic approach, which may be slower to develop, but has the buy-in of entities which are closer to and more accountable to civic society.

In addition, even if it was agreed that a mandate was preferable, is the WTO the best forum to mandate ecommerce? The WTO has a history of being secretive and not welcoming participation from civic society. In fact, it’s designed to be shielded from democratic pressure for influence. Furthermore, their principal objective is increasing trade, not necessarily developing good global trade policy which reduces poverty and inequality. So, do we really want the WTO to govern the global trade system? I realize opening everything up for discussion would create more chaos and cause obstacles to getting agreement on various issues, but I believe the secrecy is worse and the effects of a global trade agreement are much too extensive to tolerate the secrecy.

I don’t think its as much that CEPR is absolutely against free trade and against globalization. It’s that they’re against what they perceive as these built-in biases in systems which, if expanded, would lead to more corruption, inequality and poverty for “the people” and more power, wealth and influence to the multinational corporations and those who support them.