As Congress passes legislation designed to onshore and re-nationalize the production of semiconductor-based integrated circuits, the hype of the industry backers of this plan proclaims that “The Future is Built on Semiconductors.”

Is it, now? It would be more accurate to say that the “The Present is built on Semiconductors” and that “The Future will come from somewhere else.” Any company that wants to lead us into the future will not be making the tiny, incremental but very expensive improvements in chip technology and production that are currently possible. The businesses that are being subsidized under the branding of “the future” are really stuck in what will soon be the past.

The semiconductor industry is mature and highly consolidated. The concentration occurs because a highly efficient division of labor evolved between the design of integrated circuits and the fabrication of chips needed to implement the design. The design function is a reasonably open and competitive arena in which anyone with good ideas can make a mark. The fabrication part, on the other hand, has become so hugely capital intensive that investors in new facilities must commit upwards of $20 billion to the project, and that creates a need for such huge scale in production that there is not room for many suppliers. Half the world market comes from one supplier, Taiwan’s TSMC. The one company that refused to go along with this division of labor, Intel, is suffering for it. Their vertically integrated, less specialized structure simply could not keep up.

The industry is fond of invoking “Moore’s Law” and pointing to five decades of exponential efficiency gains. The gains come from increases in the number of transistors that can be crammed onto one chip. This triumphalism ignores two salient facts.

First, all of the Moore’s Law progress dates back to the invention of metal-oxide semiconductors back in 1959, which enabled the use of metal–oxide–silicon field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) to produce integrated circuits. MOS chips exceeded the transistor density of its technological predecessor, known as bipolar chips, in 1964. Not coincidentally, Moore proclaimed this law in 1965. MOSFETs technology was tossed into the competitive marketplace and produced the rapid improvements in manufacturing costs and transistor density at the exponential rate that that we have come to encapsulate by the term “Moore’s Law.” Because of the role of intensely competing firms and the inability of Bell Labs to patent the transistor, a better label would be: “Moore’s extrapolation of the effects of Adam Smith’s law.” That process has been going on for almost 60 years. But no one aware of industry realities thinks it will continue to go like that. It is slowing down. It is reaching its limits.

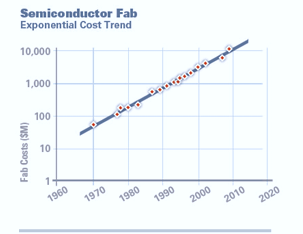

Second, the heralds of Moore’s Law almost never talk about the regression line shown below. Let’s call it Natural Law just for fun: all of those Moore improvements have been steadily accompanied by increases in the cost of the capital equipment needed to build chips. The slope of the line is not that different from Moore’s Law anymore.

The innovation trajectory that transformed the chip industry and with it, the entire information technology environment, is nearing its end. This doesn’t mean that digital technology isn’t still a major source of innovation and societal transformation. The big jumps in capacity, however, are more likely to come from software and service innovation and cyber-physical implementations – or from some completely unexpected bio-physical angle – than from advancements in MOSFETs integrated circuits.

If people think dumping big government subsidies into the chip industry is an innovation policy that will win the future, they are going to be deeply disappointed (and this assumes that the term “win the future” has any serious meaning, which it probably doesn’t). If private capital is unwilling to risk $20 billion on a new chip plant (and it doesn’t seem all that forbidding, given that someone has offered to pay $44 billion for Twitter), then it’s not at all clear that taxpayers should be doing so and that the expected return on this investment is worth it. It’s possible that, as the capital requirements of fab plants increases, we have reached the point of diminishing returns, and we should look to new industries and new sectors.

One saving grace is that the Chinese seem to be suffering from the same fallacy. They, too, are looking in the rear view mirror and attempting to overtake the U.S. in chip technology by retracing the historical steps of their competitor, only using government subsidies instead of market competition. The panic seen in the U.S. government over Communist Party 5-year plans proclaiming that they will achieve X level of technological progress in Y years and ensure that Z percent of the domestic market will be supplied by Chinese firms is truly ludicrous. Didn’t the collapse of the Soviet Union lay to rest the old Stalinist idea that the Big State can best develop industrial technologies? At least when the Soviet Union triggered the space race they actually were a tiny bit ahead of us in some technological niche of the ecosystem. The most important Chinese innovations are coming from private firms competing in global markets, such as ByteDance, not from 5 year plans, and they are targeting areas where the market indicates the best returns are.

Has Intel turned into a State-Owned Enterprise? Have the U.S. policy making elites turned into CCP acolytes? Someone needs to remind Washington that U.S. tech progress has come from competition, domestic and international R&D collaboration, and free trade, and that is truly where the U.S. has an advantage.

Dr. Mueller,

Thank you for this excellent post. It should be noted that innovation in silicon is still an ongoing process, and MOSFET could someday be replaced by FinFET with sufficient scaling. There are also entirely new paradigms being explored, from the “bio-physical” you mentioned to carbon nanotube (CNT) and graphene-based computing which may in the future become viable — it remains to be seen.

I think the crux of the issue is that in displacing the capital costs for fabrication onto a central locus like TSMC (supported by the Taiwanese government as a national priority) and saving one’s capital for research and development in design, a weakness in the global supply chain has been created. As demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, global-scale disruption to the semiconductor supply chain can be impacted by something as simple as labor shortages. Downstream, in 2020 this affected even auto manufacturing utilizing stock chips mass produced on relatively antiquated nodes. Ultimately, to your point about where 50% of global supply comes from, we are one crisis in the South China Sea away from losing half the world’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity.

The semiconductor supply chain is incredibly complex, and we haven’t even discussed access to rare earth metals. If you look at the networks of the full chain of semiconductor manufacturing from fabrication, packaging, assembly, test, and integration — the more routing you have for that product through international borders the “leakier” the chain and the more chance you have for hardware subversion at the low end of risks and simple disruption to supply at the high end. If there is a market failure due to capital costs to enter the fabrication business, then the USG should step in like it is in order to correct the problem, even if that vulnerability was self-induced two decades ago.