When the NTIA made its announcement to end its historic role overseeing the IANA functions, ICANN was eager to fulfill its assigned convener role. It initiated two concurrent processes, one for developing an IANA functions transition proposal (or, as ICANN prefers to frame it, its “stewardship transition”) and another on enhancing ICANN accountability. The former dealt with implementation of the registries for names, numbers, protocol parameters; the latter specifically with holding ICANN the organization responsible for decisions it took (e.g., board decisions dealing with DNS policy or other areas).

We are now almost six months into these processes. Where do we stand?

While off to a rough start, the process for developing the IANA transition proposal is proceeding appropriately. ICANN’s initially proposed organizational structure was widely rebuffed in public comments from stakeholders, with concerns voiced about scope, composition, procedures, etc. ICANN staff adjusted their proposal accordingly (although it choose to conveniently ignore some widely made points). Ultimately, a revised IANA Stewardship Transition Coordination Group (ICG), with members selected by their stakeholder groups, was seated. The respective naming, numbering and protocol stakeholders are ideally now beginning to develop their respective proposals for the IANA transition (UPDATE: a Cross Community Working Group at ICANN has been in discussions since July and recently completed an impressive draft charter to develop a transition proposal for names). According to the ICG’s draft charter, it will receive these stakeholder-developed inputs, assess and interact with the stakeholders as needed to present a cohesive proposal to the NTIA by next September.

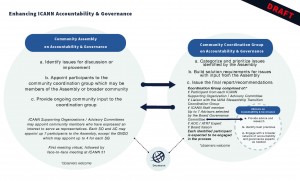

For the accountability process, it’s too early to pass judgement, but the signs are not good. In Singapore and London face to face meetings were held to discuss how to advance the situation. In May, ICANN solicited comments from stakeholders which did not ask any questions related to actual process. Nonetheless, earlier this week, the ICANN staff and CEO Fadi Chehadé met with ICANN’s SO/AC leaders, and proposed an organizational structure for determining ICANN accountability enhancements. They described a structure consisting of:

1) a Community Assembly (CA), tasked with identifying issues. Each SO/AC would appoint up to 7 participants to the CA, except the GNSO which may appoint up to 4 participants for each stakeholder group. The CA would be open to observers.

2) a Community Coordination Group (CCG) that would categorize and prioritize issues, build solution requirements, and issue final reports and recommendations. The CCG would be comprised of one participant each from the GNSO, ASO and CCNSO, a liaison with the ICG, an ICANN staff member, an AoC/ATRT expert, a board liaison, and up to (7) governance, organizational, and legal expert advisers selected by ICANN’s Board Governance Committee (BGC). The CCG would also be open to observers.

Chehadé urged all the SOs and AC chairs to move into alignment and support the proposal. However, several questions were raised and flaws noted by SO/AC leaders on the call and afterward. The registries were immediately accused by Chehadé of creating an environment of “mistrust” for simply expressing their viewpoint. GNSO stakeholder groups were quick to point out:

- Why is it necessary to create a new structure, instead of a Cross-Community Working Group (CCWG)?

- Why is this structure being presented as a de-facto decision? Why weren’t stakeholders engaged earlier in the discussion so as to provide input to it?

- What is the viability of having just one representative on the CCG for the GNSO’s many diverse stakeholder groups?

- What is the rationale for seven board appointed advisers?

All are relevant questions. If ICANN is to be perceived as a stable governance organization, it needs to rely on documented processes for decision making, not ad-hoc organizational creations which can be used opportunistically. Furthermore, ICANN needs to acknowledge that it (the organization) has its own interests in the outcomes of these processes. This is precisely why NTIA requested that ICANN strictly act as a convener for the transition process. The enhancing accountability process is no different. Instead of crafting its own proposal, ICANN should have simply asked for proposals. Regarding the composition and operation of the CCG, what is the exact role of the advisers? Undeniably, they would wield great influence. Given this, it seems a conflict of interest that ICANN’s board select these individuals and that they might have anything other than an advisory role. Moreover, why is so much power afforded to the CCG? Despite calling it a “coordination group,” the CCG as envisioned by ICANN has far more power than its ICG complement. A more consistent approach would have the CCG receive issues and possible solutions from the CA, assess and interact with the experts and CA to refine, then generate recommendations that would have the support of all participating stakeholders.

1 thought on “A tale of two processes”

Comments are closed.