Background

The international trade in hardware, software, and content complicates many cybersecurity challenges. Domestic regulations and enforcement may fall short of their intended aims when foreign criminals and governments are out of their jurisdiction, and cheap insecure technologies proliferate worldwide. In response, some security experts have looked to restricting trade as a mechanism to promote cybersecurity, or to implement some form of arms control. And yet, as with any restriction on trade, these proposals have major, potentially detrimental economic consequences.

What follows is a typology of trade regimes, and the expected economic challenges associated with their use. Many of these ideas were formulated at the 2018 Harris School’s Inter-Policy School Summit which this year focused on the topic of Trade and Cybersecurity. I would like to thank my team members from the Workshop: Erik Ernesto Bacilio Avila, Edgar Braham, Luis Gonzales Carrasco, and Lina Skoglund.

Mechanisms for Restricting Trade

Trade restrictions have been used for a wide variety of purposes: promoting nascent industries, protecting politically influential sectors, and regulating the spread of dangerous goods. What makes cybersecurity such a difficult topic for trade restrictions is the degree to which it serves dual-use purposes (military and civilian). For example, intrusion software can be used by an enterprise for security, and by a government for surveillance. And yet, the mechanisms to limit trade are not new, but grounded in existing organizations and processes.

While not intended to be comprehensive, the following framework attempts to explore the various mechanisms that are or could be used to restrict trade either of cybersecurity products or general IT products for cybersecurity reasons.

– Export Controls

The Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods provides a 42-country wide multilateral export control regime. This successor to the Cold War era technology export control program started in 1996, Wassenaar tried to upgrade its standards with a 2013 amendment that added an export restriction to internet based surveillance systems.

The Missile Control Technology Regime (MCTR) is not a treaty, but “an informal political understanding” that controls exports of missile technologies through established Guidelines. These Guidelines reference specific equipment, software and technologies that could proliferate missiles with greater range and payload capacity. This informal restraint of trade, has not had a significant effect on cybersecurity products.

– Tariffs

Article XXI security exception is a World Trade Organization mechanism which allows an exception to the Non-Discrimination principle in the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) allowing a country to raise trade barriers against a partner or import flow based on a National Security threats. Similar security exceptions are made to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) where Article XIV bis allows for the “protection of essential security services.” On March 1st, President Trump stated that he would use the GATT exception to promote the US Steal and Aluminum industry. By default, the WTO Information Technology Agreement sets the tariffs on IT products to zero for over fifty participating countries including the US, EU, Russia, and China. For now, the ITA appears to have limited the use of tariffs to promote a domestic cybersecurity industry.

– Investment Restrictions

As a US-specific inter-agency body, The Treasury-led Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) reviews the national security implications of acquisitions of US businesses by foreign actors. Upon review, CFIUS can then recommend that the President block these acquisitions. Cybersecurity, with its dual use potential, increasingly has been cited as a factor in CFIUS decisions. This blog has previously noted how concern about Chinese access to US markets, has led CFIUS to make anti-competitive blocks. The US program is not unique, other nations including Canada and Germany have similar review processes.

China’s Cloud Computing Regulations present another kind of investment restriction with significant impacts on cybersecurity. With regulations requiring local partners and requirements to reveal proprietary code, the country maintains strict control over cloud services. While this control may have certain cybersecurity intentions, its ends are more likely to enable domestic surveillance while hindering foreign surveillance.

– Localization Requirements

While the cloud computing requirements in China emphasize ownership limitations, localization requirements have been adopted more widely, either deployed in a specific sector like telecommunications metadata in Germany, or all personal data in Russia. More informal targeted localization requirements have also been propagated in the United States. The federal government efforts to prohibit Kaspersky Antivirus and Huawei have been banned from bidding for US government contracts after accusations of enabling foreign espionage. These government actions have led to American companies responding in kind resulting in a de facto ban.

A Typology

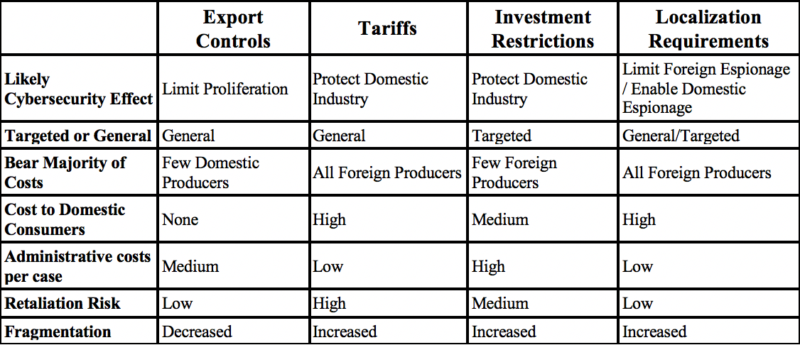

In an attempt to clarify analysis of trade-related cybersecurity restrictions, I have developed a table which relates the different trade control mechanisms to the following dimensions: 1) their effect on cybersecurity; 2) the distribution of costs; 3) how targeted or generic the restrictions are; and 4) the opportunities for retaliation or fragmentation they create.

– Cybersecurity Effect

The purported cybersecurity effect of the policies described above is limited. Rather than directly providing information assurance to domestic consumers or enterprises, these policies instead seek to limit proliferation, protect domestic industry, or limit foreign espionage. And yet many of these policies may have a net negative effect on the domestic populace. If the expense of cybersecurity products rises, or domestic espionage is made easier, the net effect would be to undermine security.

– Targeted or Generic

The effect of these policies can be considered to be either generalized through a widely applicable standard, or targeted (as with Investment Restrictions) at a specific enterprise. The scope of these policies has clear consequences on the likely impact for security, potential costs, and long-term effects on norms.

– Costs

Who bears the brunt of the cost of trade restrictions? The subsequent chart is intended to address how producers, consumers, and governments might distribute the costs. Producers in this context represent the global IT industry (including the cybersecurity sector). Consumers are those individuals and enterprises that use these goods. Governments will face administrative costs in the enforcement of these provisions.

– Retaliation and Fragmentation

National decisions about trade restrictions do not occur in a vacuum. Nations will respond to each other in their interest. Particularly with arbitrary tariffs, the likelihood of retaliation with counter tariffs is high. In contrast, other policies might not result in retaliation, but might lead to norms which will further fragment the Internet. As countries seek to align the Internet with nation specific rules, they are likely to inhibit the cross-border flow of goods and services and change the character of the Internet from one country to another.

Table: Classification of Trade Regimes

This framework helps to clarify some of the tradeoffs and consequences of regulating cybersecurity through existing trade regimes. There are important distinctions of purpose, how targeted the program is, who will bear the costs, and how other countries might respond. While no program is without some cost, these factors should bring pause to anyone hoping to leverage the international trade regime as a mechanism to bring peace.

Lessons

For example CFIUS, while unlikely to affect domestic producers, has a high risk of trade backlash and creating restrictive norms, while export control regimes are unlikely to see trade retaliation but do punish the domestic industry of cybersecurity services if they limit legitimate research and sale. The costs will be faced by someone in the market.

At present, the potential benefits of these proposed trade regimes seem to fall mostly to governments under a national security paradigm. However, even if these programs were targeted to limit the flow of vulnerable software, the typology above would remain true. By limiting the consumer choice to use foreign goods, governments are making critical value judgements on behalf of their citizens.