Unpacking the digital political economy

As the summer begins, with long awaited in-person conferences and intensive research activity, we are busily developing the Call For Papers for our annual IGP conference for fall 2022, which will focus on the global digital political economy. What scholars and policy makers used to call Internet governance no longer exists. Every policy problem that involves the Internet is now a subset of larger policy problems posed by a globally networked system of digital technologies, capabilities and services. To understand these problems, scholars need to focus on the digital political economy as a whole.

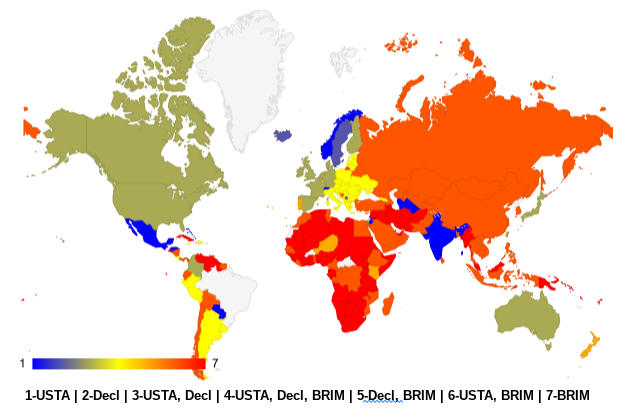

Take the recent Declaration for the Future of the Internet released by the USG last month. Our quick take noted it as a useful normative initiative, but also suggested it fell short in promoting areas like digital/ICT trade. Where does the Declaration intersect with great power competition (like the US and China) and efforts to influence trade? The Figure below maps out states aligned with: US bilateral agreements in IPR, free trade, investment (USTA); the Declaration (Decl); and Belt & Road Initiative Memoranda (BRIM).

Bright blue states are aligned only with US trade agreements, while bright red are aligned only with the B&R initiative. The lighter greenish and orange shades represent different combinations of the three efforts. They highlight the relative importance of economic trade between powerful adversaries (US, China, Russia), and the cohesion between US trade agreements and the human rights norms of the Declaration. In the middle are the yellow states in Eastern Europe and parts of South America, which highlight the importance of global trade and the role of the Declaration. These states participate in all three efforts and probably represent states most up for grabs in a tech cold war view of the world. How independent (isolated?) Brazil appears is interesting. The US and Brazil have a trade and economic agreement but it doesn’t appear to be enforced currently, and the South American continent appears relatively unsettled. On the other hand, the BRI includes African states almost to the total exclusion of Western normative and trade influence.

This descriptive view just touches on the global digital political economy. It ignores multilateral efforts like WTO, WIPO or other state or industry based agreements. It invites research integrating country-level data on ICT exports/imports, data flows, financial systems, regulatory environment, etc. as well as more macro-level analysis.

W3C attempts to reinvent itself

The World Wide Web Consortium, which was founded in 1994 by Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee and sets standards for Web technologies, is undergoing important changes in its governance. One of its original host organizations, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (MIT/CSAIL), is ending its status as host at the end of the year. Some are questioning Director Berners-Lee’s role as “philosopher-king” with bottleneck authority over consensus determinations. There is talk of making it an industry-led nonprofit but also some concern about whether the major platform/ browser operators can cooperate adequately. The long-time unincorporated organization has filed incorporation paperwork in Delaware. Given the important role of Web standards in determining the future of advertising and privacy on the Internet and the push in some quarters for so-called Web3, the future of Web standards governance is important. This is a real test for the nongovernmental, networked governance that has been so crucial for the Internet.

India’s new cybersecurity directive under fire

On April 28, the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In), which is the nodal agency tasked with performing cybersecurity-related functions, issued directions relating to information security practices, procedure, prevention, response and reporting of cyber incidents for Safe & Trusted Internet (Directions). The directions come into effect from 27 June, and apply to “all service providers, intermediaries, data centers, body corporate and government organizations” (entities). Non-compliance is punishable by imprisonment for a period of up to 1 year or fine of up to INR 100,000 or both. These directions have come under heavy criticism by various civil society, digital rights and international organizations, industry bodies.

Obligations include the requirement for all entities to connect their infrastructure system to a Network Time Protocol (NTP) server of National Informatics Centre (NIC); National Physical Laboratory’s (NPL) or traceable back to above. NTP is a networking protocol used to synchronize computers’ internal clocks to a common time source. The requirement has been heavily criticized as it may impact the functionality of companies’ systems, networks, and applications and introduce security vulnerabilities.

Entities must report cyber incidents within 6 hours of identification of such incidents. Industry players have called the 6 hour reporting window unrealistic and are demanding a more reasonable 72 hour timeframe. The reporting mandate also goes beyond the category of cyber incidents provided under the 2013 CERT-In Rules and includes ten new categories of incidents including data breaches and leakages, unauthorized access to social media accounts and attacks on payment systems amongst others. There is no guidance on the threshold, severity and scale of the incidents that are to be reported to CERT-In. This places the burden on various entities to assess what qualifies as a cyber incident. Recognizing this gap the CERT-In is reportedly attempting to provide definitional clarity and guidance through FAQs that are yet to be published.

The directions require entities to take action or provide information or any assistance to CERT-In towards which they must designate a point of contact to interface with CERT-In and maintain logs of all their ICT systems. The logs must be maintained for a rolling period of 180 days and within Indian jurisdictions so it is accessible for CERT-In when required. The data retention and data localization mandate increases the cost of operations, creates security vulnerabilities and is also a threat to the privacy of users.

Organizations that provide Virtual Private Network (VPN), Virtual Private Server (VPS) and cloud services, as well as data centers mandated to retain a wide range of user data for 5 years or longer if mandated under law. The data points that the listed service providers will need to store include names of users, duration and dates of service subscription or use, purpose of hiring service, users’ internet protocol (IP), email addresses, validated address, contact numbers, and even the IP address and timestamp used at the time of registration or service initiation. VPNs or other services often do not store any user data as they are designed to protect anonymity and privacy. The data retention mandate will have significant implications for such service providers, and large VPN companies like NordVPN and Proton VPN are threatening to pull out of India. The mandate is also an attack on users’ privacy and places users of these services at risk of exposure and surveillance.

Data retention requirements are intense. Virtual assets service providers, virtual asset exchange providers and custodian wallet providers are required to maintain information relating to KYC and financial transactions records for a period of 5 years. Transaction records must be maintained in such a manner so as to enable reconstruction of each individual transaction. Not only does this direction increase the burden on financial intermediaries it may also be an overreach as CERT-In seeks to obtain data which may not have anything to do with cyber security.

First ever sanctioning of crypto blender provider

States’ use of intermediaries in governing transnational crypto flows and cybercrime continues to expand. The US treasury recently sanctioned Blendor.io, a virtual currency mixer which was allegedly being used for money laundering by North Korea. A cryptocurrency tumbler or mixer is a service platform that mixes potentially identifiable funds, improving the anonymity of transactions. Blender.io failed to implement Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism policies, which allegedly aided state-sponsored hacking groups like Lazarus to launder funds from illicit activities. This sanction highlights that while virtual currency transactions might be decentralized and anonymous, it can always be regulated at the level of intermediaries. The treasury is working towards identifying more of these intermediaries to tackle increasing use of digital assets to aid criminal and terrorist groups. Meanwhile other countries like India continue to explore ways to tax capital gains from digital assets in order to limit the free market of cryptocurrencies.

Years ago, we would debate over a “narrow” vs “broad” approaches to IG (Kurbalija).

What I understand from this post is that not even the broad approach makes sense anymore — we are experiencing the full digitization of our society and the correspondent multitude of policy goals (Murray’s Communitarianism).

Thanks for sharing the newest routes to your theories, Prof. Mueller.

—

Another interesting fact is the vacuum about Brazil and the difficulty to position us as per the digital political economy lenses.

Thanks for your comment, Sergio!

We would be interested in hearing more about Brazil and the reasons for its stance on the Declaration and what direction you think it is going.

Dear Professor, I missed your reply — and unfortunately, I don’t have a complete answer to it at the moment, and I am happy to investigate.

I have a few guesses.

A. There is wording in the Declaration that might not necessarily cope with the government’s current approach to digital political economy topics.

Among other issues, I cite two.

(A. 1) We are a few months away of our general elections’ (incumbent President Bolsonaro and former President Lula are nose-to-nose), and it might not be strategic to commit to some related terms of the Declaration.

(A.2) Huawei/ZTE/others have not been banned from the rollout of our public 5G network.

The country is following the risk-based assessment approach, and Huawei/ZTE/others are definitely not banned from building the largest telecom network of the South hemisphere.

Chinese vendors will hardly serve as suppliers to the future private government broadband telecom network (a subset of the Brazilian network that shall arise as a result of the 5G spectrum auction from 2021 and the international calls for a ban), due to corporate governance standards set at the auction. Note that the regulations for the gov network do not focus cyber security parameters; instead, they cite public corporate governance rules.

Furthermore, I also hear mixed feelings and expectations around the promises of the Open Ran route from both policymakers and private firms. (i) Senior sectorial policymakers have seen policy-driven standard-setting not delivering in the past. (ii) Operators are reluctant because of (ii.a) the complexity it adds to would managing a multitude of suppliers, and (ii.b) simply because it can take too long to actually deliver its promises. Many prefer to handle verticalized solutions and to wait for the Open Ran policy and technical fora to gain more momentum.

B. I am not aware of how much leeway the Brazilian diplomacy and tech policymakers actually had to negotiate the text.

It took us 20 years to accede to the Budapest Convention for two main reasons: (i) the intellectual property commitments would not relate to Lula-Dilma’s digital policies (some stakeholders argued that it could negatively impact Brazilian digital inclusion and access to knowledge policies), and (ii) it was arguably against the country’s foreign policy tradition to join a treaty at which it did not take part in the construction phases. In the latter, some would go farther and label that the BC was not an “international treaty”, but just “an invitation to comply with a EU-US bilateral arrangement”.

C. Most importantly, though, Presidents Jair Bolsonaro and Joe Biden are still working on building their relationship. It can take some time.

Best,

Sergio

Dear Professor, I missed your reply — and unfortunately, I don’t have a complete answer to it at the moment. I am happy to investigate.

I have a few guesses.

A. There is wording in the Declaration that might not necessarily cope with the government’s current approach to digital political economy topics.

Among other issues, I cite two.

(A. 1) We are a few months away from our general elections’ (incumbent President Bolsonaro and former President Lula are nose-to-nose), and it might not be strategic to commit to some elections-related terms of the Declaration.

(A.2) Huawei/ZTE/others have not been banned from the rollout of our public 5G network.

The country is following the risk-based assessment approach, and Huawei/ZTE/others are definitely not banned from building the largest 5G telecom network of the South hemisphere.

Chinese vendors will hardly serve as suppliers to the future private government broadband telecom network (a subset of the Brazilian network that shall arise as a result of the 5G spectrum auction from 2021 and the international calls for a ban), due to corporate governance standards set at the auction. Note that the regulations for the gov network do not focus on cyber security parameters; instead, they cite public corporate governance rules.

Furthermore, I also hear mixed feelings and expectations around the promises of the Open Ran route from both policymakers and private firms. (i) Senior sectorial policymakers have seen policy-driven standard-setting not delivering in the past. (ii) Operators are reluctant because of (ii.a) the complexity of managing multiple suppliers instead of buying a bundle solution, and (ii.b) simply because it can take too long to actually deliver its promises. Many prefer to handle verticalized solutions and to wait for the Open Ran policy and technical fora to gain more momentum.

B. I am not aware of how much leeway the Brazilian diplomacy and tech policymakers actually had to negotiate the text.

It took us 20 years to accede to the Budapest Convention for two main reasons: (i) the intellectual property commitments would not relate to Lula-Dilma’s digital policies (some stakeholders argued that it could negatively impact Brazilian digital inclusion and access to knowledge policies), and (ii) it was arguably against the country’s foreign policy tradition to join a treaty at which it did not take part during the construction phases. In the latter aspect, some would go farther and state that the BC was not an “international treaty”, but just “an invitation to comply with a EU-US bilateral arrangement”.

C. Most importantly, though, Presidents Jair Bolsonaro and Joe Biden are still working on building their relationship. It can take some time.

Best,

Sergio