Disinformation during emergencies (DiE) can critically undermine government efforts to mitigate socioeconomic harm and damage the relationship between the state and citizens. With the production of nuclear power growing in multiple countries and widespread concern over generative-AI-fueled disinformation online, we are researching the impact of DiE on transnational nuclear emergency responses. Over the next few weeks, this blog post series will lay out our ongoing research from conceptualization to data analysis and policy recommendations, and we invite your observations and feedback in the comments on any part.

Research design

Successful DiE threat assessment and building an effective response requires access to and researching large digital media datasets and actual case studies. However, the extent to which generative AI technology is used in online disinformation is uncertain, and nuclear emergencies are relatively rare events. Given this, we examine two nuclear emergency cases during a period of rapid development of online content moderation governance and growing awareness of state influence operations and disinformation, including: 1) the natural disaster caused Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FNPP) nuclear emergency, and 2) the man-made occupation by Russian forces of the Zaporozhzhian Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) in Ukraine.

Both cases fall under the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) definition of a nuclear emergency, which is a non-routine situation or event that requires prompt action to mitigate a hazard and adverse consequences to human life, health, property, and the environment. Both cases highlight the disruptive power of disinformation on emergency communication efforts. We monitored Western and indigenous social media platforms (Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, VK, Weibo, Naver) and Russian and Ukrainian Telegram channels. Traditional media channels owned or sponsored by Russia, Ukraine, China, South Korea, and Japan also provided data. Additionally, official statements from governments, private companies, and the IAEA were incorporated.

Conceptualizing disinformation as propaganda

Unlike much current work, we utilize established propaganda/communications theories rather than assuming that disinformation disseminated online are sui generis. Drawing on the rich history of propaganda analysis and connection to the role of the state and political economy, we conceptualize and analyze DiE using Jowett and O’Donnell’s (2018) propaganda and persuasion framework (see also George, 1954; Krippendorf, 2019 for some history of propaganda analysis). Propaganda analysis has two general purposes, 1) description or summarization of the propagandists’ message, and 2) inferences or interpretation of intent, strategy, and calculations behind propaganda messages. (George, 1954, vii) As Ithiel de Sola Pool (1960) explains in his review of Alexander George’s seminal work on the U.S. government’s Federal Broadcast Intelligence Service efforts to interpret Nazi propaganda during WWII, analysts relied on qualitative interpretations, often intuitive assessments of broadcast content, which proved to be remarkably accurate in predicting outcomes. Informed analysis of propaganda can reveal underlying policies and strategic intentions, suggesting that the creation of propaganda is closely tied to the policy objectives of the propagandists, aiming to shape public perception in line with these objectives. We use this approach to generate a deeper understanding of observed DiE and develop appropriate institutional responses.

The categorization of propaganda into black, gray and white provides a nuanced framework for understanding the tactics employed. Black propaganda entails the deliberate spread of falsehoods, crafted to deceive and manipulate without disclosing the true origin, thereby undermining the target audience’s ability to discern information credibility. Gray propaganda occupies an intermediate position, featuring ambiguous sourcing that complicates attribution and fosters uncertainty. In contrast, white propaganda involves transparently attributing information to a known source, with the intention of influencing the audience toward a specific perspective or agenda. These concepts provide an effective lens for analyzing the strategic intent, transparency, and veracity inherent in influence operations employed by the state and non-state actors across multiple media channels during nuclear emergencies.

<A satellite image reveals unidentified objects at the ZNPP, with Ukrainians alleging that Russians planted explosives, intending to exploit the ZNPP as a nuclear terrorism hostage. Source: Planet Labs>

<A satellite image reveals unidentified objects at the ZNPP, with Ukrainians alleging that Russians planted explosives, intending to exploit the ZNPP as a nuclear terrorism hostage. Source: Planet Labs>

For ZNPP, we seen Russian and Ukrainian governments propagating false narratives about the plant’s safety, including black propaganda and disinformation efforts, often perpetuated by lack of factual verification. It demonstrates how both sides disseminate false claims, such as Ukraine alleging Russia planted explosives at ZNPP for nuclear terrorism, Russia accusing Ukraine of developing chemical and biological weapons in their nuclear facilities, and the ongoing argumentation on both sides regarding who bears responsibility for the Kakhovka Dam explosions and shelling around the ZNPP. Notably, the absence of substantial, public evidence enables governments to shape narratives based on their authority, grounded in their monopoly on force or regulatory roles.

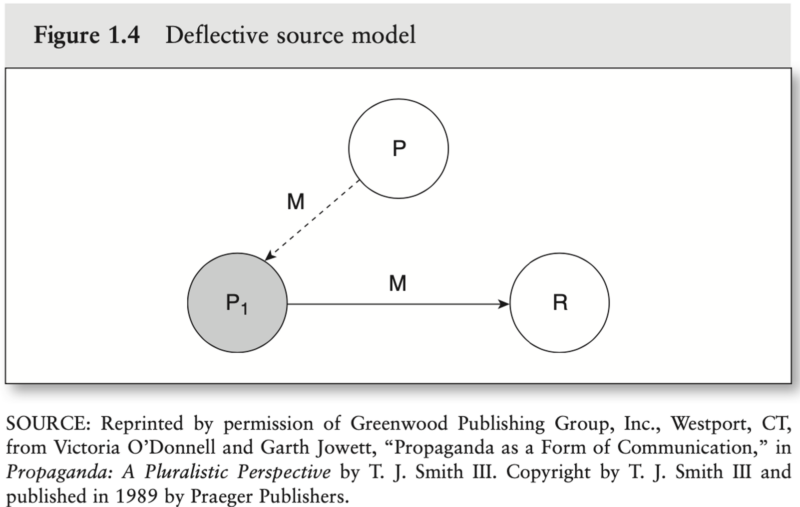

The Deflective Source Model (O’Donnell and Jowett, 1989) delineates the mechanism through which false assertions from each party are disseminated across diverse media channels to mold the perceptions of target audiences. As depicted in Figure 1.4, the propagandist (P) orchestrates the creation of a deflective source (P1), which assumes the role of the apparent source of the message (M). The recipient (R) interprets the information as originating directly from (P1) and does not link it to the original propagandist (P). For instance, within the context of the ZNPP, the Kremlin (P) selectively presents its unambiguous information suggesting that Ukraine attempted to develop chemical and biological weapons at the ZNPP (M). This information is then conveyed to Russian state media, Telegram and social media channels (P1). Subsequently, pro-Russian social media users and the public (R) are exposed to this black propaganda, leading to ambiguity regarding the accuracy or veracity of conflicting information.

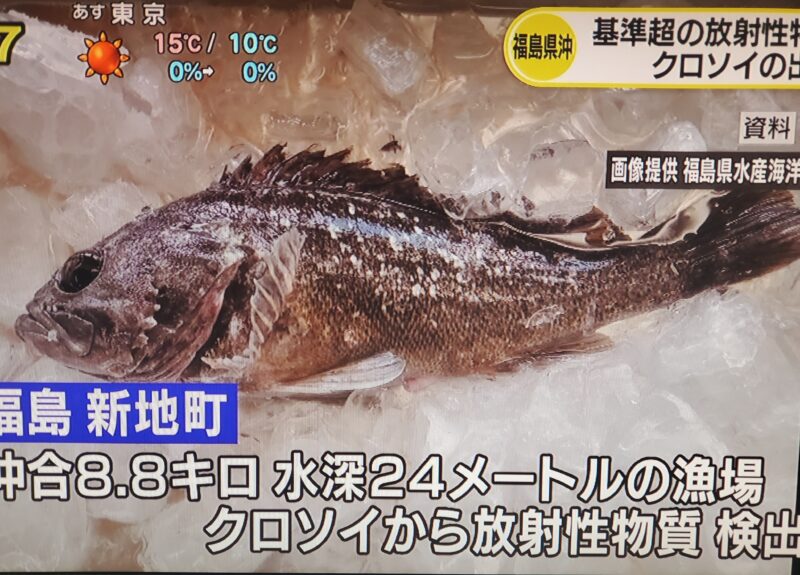

<A depiction of fish exhibiting radioactive contamination and mutations captured in Fukushima before the commencement of water discharge. Propagandists reproduce these images to substantiate their assertions, persisting even after the initiation of water discharge. Source: NHK>

<A depiction of fish exhibiting radioactive contamination and mutations captured in Fukushima before the commencement of water discharge. Propagandists reproduce these images to substantiate their assertions, persisting even after the initiation of water discharge. Source: NHK>

Within the context of the FNPP, a mixture of misinformation and disinformation emanates from gray propagandists situated in China, South Korea, and Japan. Their objective is to sway East Asian populations into believing that the Japanese government is inadequately addressing the safe release of treated water into the Pacific Ocean. Notably, certain South Korean left-wing politicians actively engage in disseminating misinformation pertaining to Fukushima, transitioning from initial unknown source information about health and environmental conditions to more recent assertions regarding the discharge of radioactive water. Interestingly, a British fact-checking startup, Logically, argues that the Chinese government is actively involved in disinformation campaigns against the Japanese government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company. This involvement is evident through the dissemination of false claims in commercial advertisements on social media platforms.

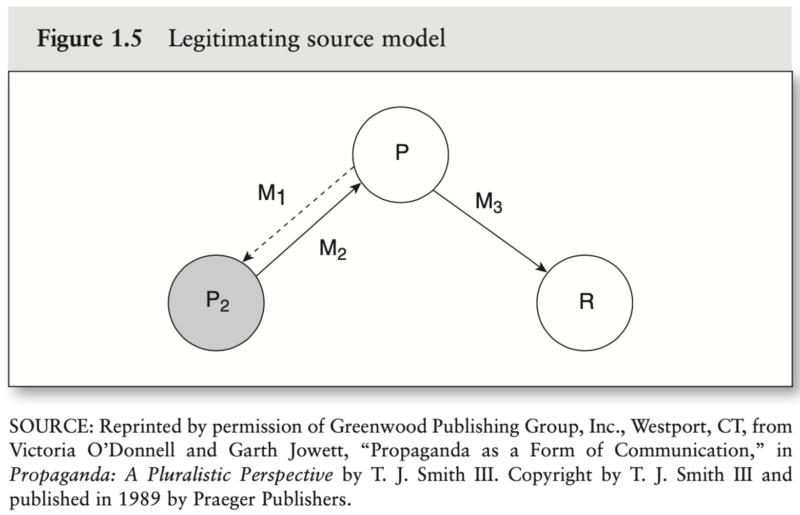

The Legitimating Source Model illustrates how South Korean and Chinese gray propagandists mutually reinforce and legitimize false claims by citing each other’s allegations within domestic media channels. In Figure 1.5, the propagandist clandestinely embeds the initial message (M1) within a validating source (P2). This message, now transformed into (M2) through the lens of (P2), is subsequently adopted by the propagandist (P) and conveyed to the recipient (R) as emanating from (P2) in the guise of (M3). This process serves to legitimize the message while concurrently distancing the propagandist (P) from its origin. The research delves into the intricate mechanisms through which South Korean and Chinese propagandists mutually reinforce their deceptive claims by cross-referencing each other’s allegations within their respective media landscapes. For instance, an unidentified South Korean source (P) asserted that the Japanese government had exerted influence on the IAEA to ensure a favorable comprehensive evaluation outcome, purportedly with the objective of garnering international support (M1). Chinese state-owned (P2) media actively disseminate such baseless allegations, broadcasting them to the public (M2). Intriguingly, South Korean left-wing media (P) echo these narratives from Chinese sources, utilizing them as references to bolster their own claims (M3) within the South Korean public sphere (R).

<An image captures the meeting between IAEA Director Immanuel Grossi and Japanese Prime Minister Kishima concerning the IAEA’s approval of Fukushima water releasement. Source: IAEA>

<An image captures the meeting between IAEA Director Immanuel Grossi and Japanese Prime Minister Kishima concerning the IAEA’s approval of Fukushima water releasement. Source: IAEA>

The dissemination of white propaganda, spearheaded by the IAEA, the Japanese government, and the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), aims to establish credibility among audiences through the presentation of scientific data, a commitment to transparency, and the involvement of independent third-party entities. The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs consistently produces and shares videos and written explanations in English, Mandarin, and Korean, elucidating the reasons behind the perceived lack of environmental threat associated with the release of treated water. In an ongoing effort to assure the international community of the water release’s safety, both the IAEA and TEPCO meticulously oversee the operation of the water purification system at the FNPP. They provide transparent data to ensure the international community remains informed and confident in the safety protocols governing the water release. Japan also extended invitations to international nuclear experts from laboratories in Canada, China, France, and South Korea to visit the FNPP. These experts were granted the opportunity to actively engage in the sampling collection process, a measure undertaken to reinforce the substantiation of Japan’s white propaganda efforts.

Countering nuclear emergency propaganda with AI and governance

In the spring of 2023, the Japanese government implemented an artificial intelligence (AI) system designed to combat black and gray propaganda by discerning and subsequently addressing false information circulating on social media platforms. In June, this system successfully detected a spurious assertion originating from South Korea, alleging a significant political donation from a high-ranking Japanese Foreign Ministry official to the IAEA. During a press briefing on July 23rd, Yoshimasa Hayashi, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, emphasized the Ministry’s deployment of AI technology for disinformation identification and fact-checking purposes. Additionally, he underscored that the Ministry regularly engages with social media platforms, urging them to remove such misleading content.

Japan’s recent initiative to employ AI in combating black and gray propaganda on online news platforms serves as a central case study for examining the government’s utilization of AI in online influence operations. Thus far, the study has not observed the use of AI as a central mechanism for generating, reproducing, or disseminating black and gray propaganda. Instead, the research has identified that the configuration and effectiveness of various influence operation tactics is often contingent on the absence of transparent and independent fact-checking agencies in specific circumstances particularly during the national emergencies.

In the forthcoming post, we’ll focus on the content moderation initiatives implemented by the Japanese government and global social media platforms through the utilization of AI-driven disinformation detection tools. The study will explore the legal frameworks across different jurisdictions, examining whether they permit collaborative content moderation endeavors between governmental bodies and social media platforms, supplemented by relevant examples. Additionally, the research will underscore the importance of establishing a governance structure independent of state influence to counteract disinformation in nuclear emergencies.