The Cyber Incident Reporting Act (CIRA), a law sponsored by a Republican and a Democratic senator, attempts to centralize data and incident reports in the hands of the federal government’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). The law would create a new incident reporting office within CISA and require companies that pay ransom after a ransomware attack to report it to the government within 24 hours, and then file a more detailed, technical incident report within 72 hours. The law does not apply to companies with less than 50 employees. The reporting requirements are enforced by means of subpoenas rather than fines.

After collecting this data and building up its procedures and capabilities over the course of 18 months, CIRO would issue monthly reports that “characterize the cyber threat facing Federal agencies and covered entities, including applicable intelligence and law enforcement information, covered cyber incidents, and ransomware attacks.”

Centralizing data

The law raises important issues about the way responsibility for cybersecurity is distributed among actors, as well as the role of centralized and compulsory information sharing in cyber security. The tendency among the general community is to support it because, well, we need to “do something” about cyber attacks generally and ransomware specifically.

However, it is difficult for supporters to explain exactly how the collection of this data would lead to tangible improvements in cybersecurity for the tens of thousands of independently managed networks and information systems. The possession of this information by the government, and the issuance of reports, simply will not have any effect on the vulnerabilities and defenses of real world organizations, even within the government. By the time a centralized agency digested the data and issued analytical reports, the specific threat that led to the incidents would be well-known and news of them disseminated via CERTS, private security firms, existing Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) and so on. One might gain a more statistically representative data set, but it is not at all clear that the costs of sustaining this new Office and the burden on covered entities, would produce a corresponding gain in public cyber security. The failure of DHS’s Automated Indicator System, created by a 2015 law that also attempted to centralize threat intel in the hands of the federal government, was cited by several students as a reason to be skeptical of this law.

The Cybersecurity Industry

One might think that threat intel and cybersecurity firms would be against the law, because this might be the beginning of a process by which the feds invade and take over their industry. But one need only read Section 2232(d)(1) to stop worrying about that. The law encourages any entity that is required to submit a cyber incident report or a ransom payment report to use “a third party service, such as an incident response company, insurance provider, service provider, information sharing and analysis organization, or law firm, to submit the required report…” This aspect of the law artificially inflates demand for the services of commercially motivated cybersecurity and insurance providers by forcing less well-equipped companies to use them to comply with the law.

But the need for companies to rely on all these “third parties” calls into question the need for the law.

There are already many companies and research centers that collect and analyze data about cyber threats and incidents, and utilize this data to help companies protect themselves. As businesses, the providers of commercial cybersecurity services and their customers are in a better position than the feds to gather and assess relevant data and use it to defend the facilities of their customers. (It is noteworthy that FireEye uncovered the Solar Winds threat before the NSA, for example.) These services have account managers and tech support to fuse threat intel with action. A centralized government agency doesn’t. And while the government might get more data because of the compulsion to report, it cannot guarantee that the data collected is of the quality and relevance needed to be actionable in the highly diverse enterprise and organizational environments that characterize cyberspace.

Crypto

One interesting aspect of this attempt to centralize data and attack ransomware is the impact on cryptocurrency. Given that its focus is ransomware, the law cannot avoid the issue of cryptocurrency, but its approach is not well thought out. It assumes that all virtual currency addresses are backed by a cryptographically-unique public key. As Joshua Weintraub, a student in the MS-Cyber program at Georgia Tech pointed out, many cryptocurrencies have multi-signature wallets, and thus no single public-key from which the address is derived. This student also pointed out that the reporting requirements could easily blur into a form of de-anonymizing or regulating crypto exchanges, as the exchanges might be required by the law to know whether people were buying crypto in order to pay a ransom.

The Vote!

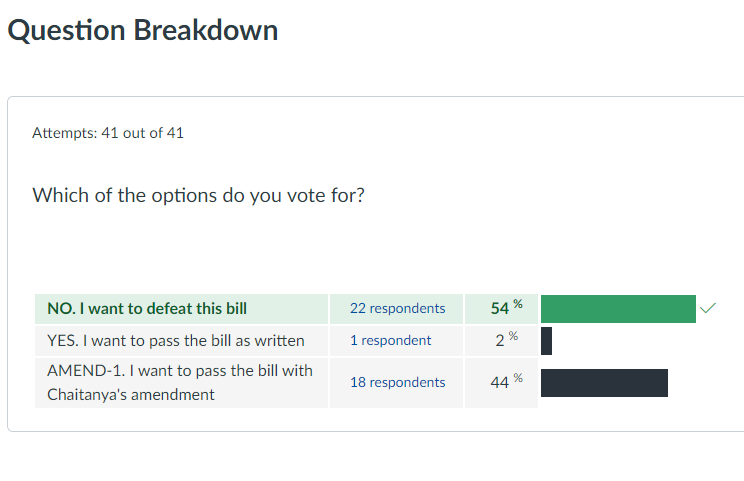

On November 2, a vote was held and the law went down to defeat by a vote of 54% against, 44% for an amended version of the bill, and 2% in favor of passing the bill as written. The bill is not really dead, however, because the vote was held in a “Congress” consisting of graduate students in the Georgia Tech class, “Information Security Strategies and Policies.” The cybersecurity policy course is a required core course in Tech’s MS Cybersecurity program. Each year, students – a mix of computer scientists, policy and management spend about 10 days discussing and debating real legislation and strive to achieve a consensus on the passage of the bill. The results are shown below.

Oh man you got all excited! 😉

On the other hand, not being required by law to sunlight ransomware payments allows companies and the security firms hired by them to keep things quiet, which in turn incentives ransomware gangs to keep at their game. It might be interesting to unpack how governments became aware of and decided to take action against REvil, and then perhaps a better judgement could be made on whether or not centralized reporting is a good or bad thing. To allow the status quo continue even legitimizes ransomware gangs who posture themselves as security services, as if finding vulnerabilities and exploiting is indeed a service and not just extortion.